Hello there!

While I anxiously await the release of Half Notes from Berlin on October 4th and the blog tour that will follow, here are the latest reviews from the critics:

Kirkus called Half Notes “A mesmerizing novel, moving and intelligent.” You can read the review here.

BookLife selected Half Notes as an editor’s pick. The review can be read here.

Alright. Enough news for now. Let’s move on to something more fun (the real reason why you signed up for this reader group)—an interesting and obscure bit of history that served as the backdrop for Half Notes from Berlin and was responsible for its genesis.

In 2002, I ran across the book Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers by Bryan Mark Rigg. Flipping through the pages, lingering over the faces of uniformed Germans with Jewish ancestry, I was captivated by one photo in particular: a photo of a wounded man in pajamas, with a bandaged head, neck, and both arms. Its caption read: “Half-Jew Ernst Prager a few days after he was shot seven times while fighting on the Russian front (last rank captain). A few months after this photo was taken, he met Eichmann about his Jewish relatives.”

I put the book back on the shelf. I couldn’t bring myself to read it. I had just turned twenty and saw the world in black and white; the idea that people with Jewish ancestry could fight for the Nazis was inconsistent with everything I thought I knew about the war.

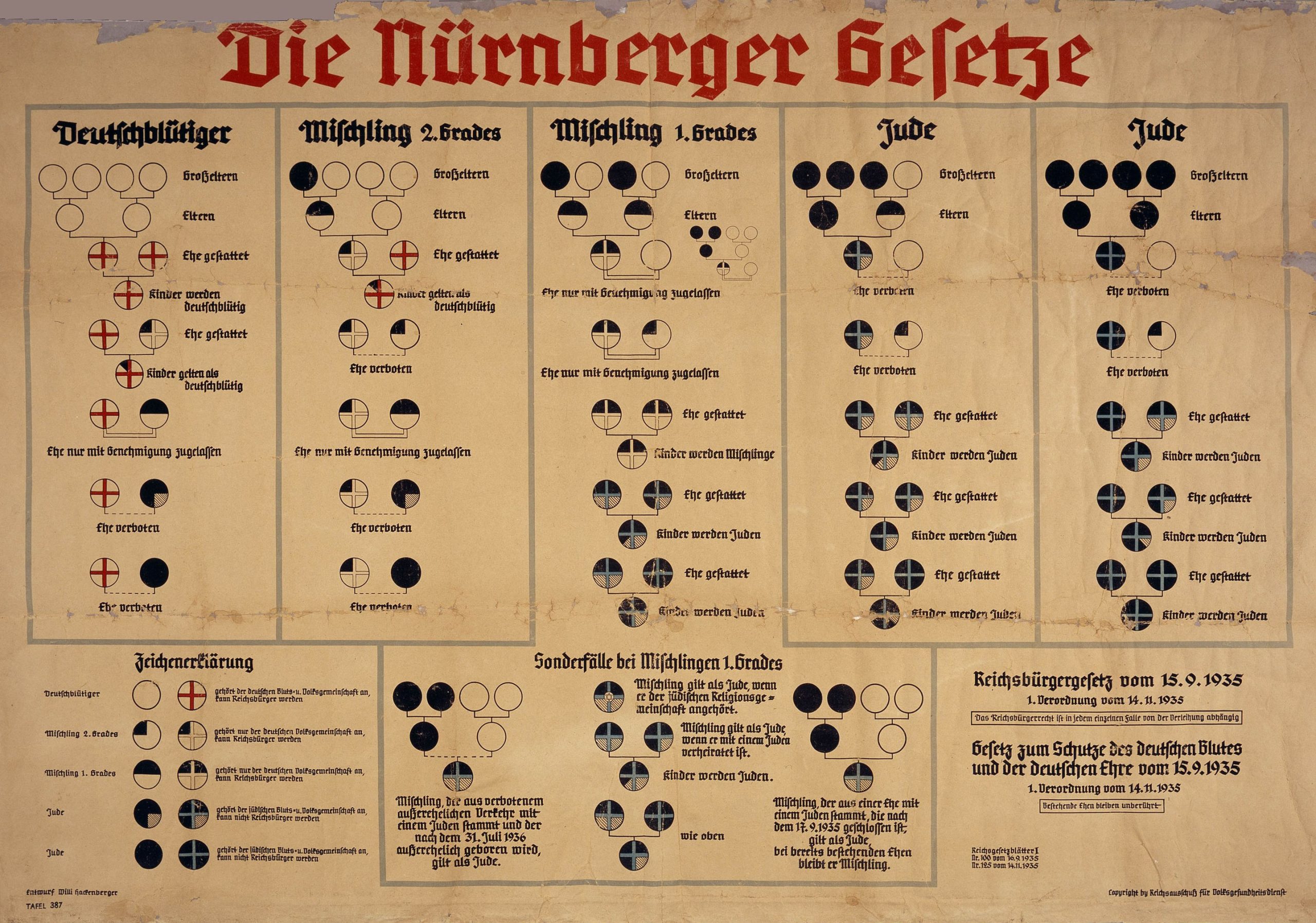

But for more than ten years, I kept thinking about Ernst Prager and his story, until I finally ordered the book and read it cover to cover. It turned out that Prager’s story wasn’t an isolated incident. There were thousands of people like Prager. They didn’t identify as Jews (so the book title was a bit of a misnomer). They had all converted to Christianity and believed they should have a place in the new Reich. They were called Mischlinge (or Mixling in English)—a racial category the Nazis invented and introduced with the Nuremberg Laws in 1935.

The way the Nazis determined who was Jewish or a Mischlinge was based on the number of Jewish grandparents a person had (3 or 4 for Jews, 1 or 2 for Mischlinge). They were extremely worried that Jews would try to escape persecution by converting and wanted to eliminate that loophole. They also wanted to prevent intermarriage, and made it illegal. However, enough Jews (converted or not) had intermarried with Germans in the previous generations and the marriages, sanctified in the Church, could not be annulled. The offspring of these legal mixed marriages were categorized as Mischlinge.

Unlike Jews, Mischlinge were not stripped of all their civil rights. Their career prospects were limited, as they were precluded from attaining higher education, joining the Nazi party, or holding any real positions of power and influence. But they could work and they could serve in the armed forces. Depending on which historian you believe, there were upwards of 140,000 Mischlinge drafted into the Wehrmacht. In fact, they were usually drafted first because they were not studying at Universities.

But as the war progressed, and the laws issued against Jews became more and more oppressive, Mischlinge soldiers who were returning home from leave began to cause problems. One Mischling recalled that when he returned home on leave, he took a stroll in his uniform with his Jewish mother. She was wearing the yellow star and they were promptly stopped by a policeman who demanded to know why a good German was walking with a Jew. When the soldier explained that this was his mother, the policeman ordered the woman to take off her star—it was unseemly for the soldier decorated with a medal to be seen with a Jew. Nazi society prized soldiers above all else that even a photograph of a child in military uniform could save a German Jew from deportation.

With the number of such awkward incidents increasing and Mischlinge soldiers demanding rights for their Jewish parents, an order came to dismiss all Mischlinge who had two Jewish grandparents from the Army in early 1940. Over 70,000 such Mischlinge (who were called first-degree) were discharged by the end of the year. Despite the order, thousands of Mischlinge first-degree remained in the armed forces. Oftentimes, their superior officers didn’t dismiss them. These Mischlinge had proven themselves in combat, and good officers knew that you don’t get rid of great soldiers in the middle of a war. Additionally, many Mischlinge ignored the orders and stayed in the hope of getting a coveted Deutschblutig certificate. This was a document that declared its bearer fully Aryan. There were only about 1500 of these certificates issued during the Nazi reign—all approved and signed by the Fürher himself.

It was believed that having this certificate not only could help a person’s career but help protect their family. The belief was misplaced. Ernst Prager got the certificate. And when he met with Eichmann, he was attempting to extract his father from a concentration camp. The fact that he was allowed to meet with Eichmann is a strong indication of how much weight the certificate carried. Although Eichmann refused to extract Prager’s father from the camp, he agreed to move him to a favored section there, which helped his father survive the war. Prager’s other Jewish relatives could not be helped in any way and did not survive.

Many people have never heard of Mischlinge, partly because this is an understudied area of WWII history, and partly because Mischlinge defy the black and white strokes with which WWII is often painted. But this is why they are so interesting to novelists, and those of us curious about obscure nuggets of history. Focusing on the life of one Mischling (Hans, the protagonist of Half Notes of Berlin) allowed me not only to explore a family microcosm that was representative of the broader German society, but to also contemplate the full range of human behavior, from loyalty and courage to cowardice and betrayal, in the context of political change.

If you are interested in reading more history about Mischlinge, I highly recommend looking at Between Dignity and Despair by Marion A. Kaplan. And of course, Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers by Bryan Mark Rigg. These two books served as my springboard into the world I imagined in Half Notes from Berlin.

Till next time!

B. V. Glants